When is an Immigrant No Longer an Immigrant? A Discussion From Experience

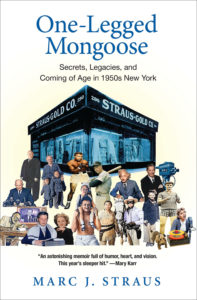

My forthcoming memoir, One Legged-Mongoose: Secrets, Legacies and Coming of Age in 1950s New York, is narrated by my 10-year-old self in the 1950s when I was between the ages of 10 and 12. My dad was an immigrant who escaped abject poverty in Ukraine at the age of 15. He went to work 16 hours a day, for one dollar an hour, six days a week on Delancey Street on the Lower East Side. He later worked in a textile store on Grand Street before opening his own business.

The Child Of Immigrants

I started working Sundays in my dad’s store when I was five and continued until I graduated from medical school. There were as many as 400 textile businesses owned by Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side. You could walk down Grand Street for at least two blocks in both directions and see nothing but textile stores.

In my book, I write about my time in the store, my uncles who worked there, and various customers. I chronicle the story of Cottonland — a retail store much like Bed, Bath & Beyond — that my father opened on Long Island in 1953. But Dad was a decade too soon.

The Lower East Side was where Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe often landed. Syrian Jews were further west on Broadway and later 5th Avenue; they often went into manufacturing handkerchiefs and tablecloths. They also lived in Flatbush, Brooklyn, and Deal, New Jersey. Italians lived in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, while the Irish had enclaves in Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens. Today, the Lower East Side has enormous numbers of Chinese immigrants.

This comes to mind today because I’m thinking about where the refugees from Afghanistan will go. How many will come to the U.S., and where will they settle? I’m not aware of a specific Afghan neighborhood in New York City yet, but I expect it exists, and perhaps it’s about to grow.

Since the founding of the country, one of the most vociferous debates has been about immigration. Who do we let in, and why? Millions of illegal immigrants are already here, most entrenched in the work system, and millions more are trying to come, most recently from Central America via Mexico.

You’ll find some people who want almost everyone admitted, while others want to keep everyone out. There are lots of people in the middle ground, and it’s been difficult to find consensus. The reality is that immigrants here legally (like my dad) or illegally (estimated at about 12 million now) are both likely to stay here for good.

In One-Legged Mongoose, the boy who narrates this story never thought of himself as an immigrant child. He admired his dad for the courage and hard work it took to come here under such adverse circumstances and make it. But he always felt American. My grandchildren hardly know or fully understand the desperate situation my dad escaped. They are so American: the oldest is at Harvard; the next Brown. Isn’t that the American story?

When Is An Immigrant No Longer An Immigrant?

What do we think of first-generation kids, as I was? Are they part-way to being American?

About three years ago there was a protest on the Lower East Side by young Chinese activists. Their issue was that the area was undergoing considerable gentrification (almost the last place in the city to do so). They were protesting that this is Chinatown, and many Chinese are losing their cheaper rent apartments.

I was sympathetic, yet also reminded by a few people who came into my gallery that the Lower East Side has always been a stopping place for immigrants — the Chinese are the most recent. My building from the 19th century until the 1960s had housed predominantly Jewish businesses, as did apartments on the street. We moved on. That’s what happens. That’s America.

Every immigrant group bought buildings when they could. Now, many purchasers are Chinese.

Every immigrant group has historically faced prejudice. There was significant antisemitism here after WWII. Our store was not legally allowed to be open on Sundays (thanks to Blue Laws) though it was our busiest day. (Payoffs to cops kept them looking the other way.)

There is no greater melting pot than the Lower East Side. I love to hear all the languages spoken on Grand Street. I love when children of immigrants know the language of their parents. My grandparents spoke Yiddish, which I pretty much came to understand. My dad spoke Polish, which he would never have wanted his kids to learn given his boyhood circumstances.

My dad was defined by what he did, but also by his dignity and sense of justice, by his smarts and hard work. His focus was on having his kids get a great education. These were important lessons for that young narrator in my book.

They are the same lessons the immigrants are teaching their kids today, in neighborhoods all over the city and country. Only the country of origin changes with every generation.

***

Marc Straus, M.D., is an oncologist and former Chairman of Oncology and Professor of Medicine. He’s also an art collector, gallery owner, author, and poet. He has authored some 100 scientific papers and edited three textbooks on lung cancer in addition to three collections of poetry.

The MARC STRAUS gallery represents 24 artists from 16 different countries. Originally focused on emerging artists not previously exhibited in New York, it is now mixed with a few mid-career and late-career artists from the U.S., Asia, and Europe. See marcstraus.com for more info.

Preorder One-Legged Mongoose: Secrets, Legacies and Coming of Age in 1950s New York, which will be released this September. Connect with Marc on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram. Sign up for his newsletter here

Mailing List